Sebastian in Art

Saint Sebastian in History and Legend

Saint Sebastian was a soldier of no certain historical standing. According to the Golden Legend, a compendium of lives of the saints, he was a Roman soldier, possibly born in Gaul, who lived in the reign of the emperor Diocletian. He declared his Christianity and as a result, on the orders of Diocletian, was shot with arrows, becoming 'as full of arrows as a porcupine is full of quills'. This 'first martyrdom' occurred on the Field of Mars (campus martius). He survived this onslaught, being nursed back to health by a virtuous widow of the name of Irene. Sebastian later declared his faith in front of Diocletian and on this occasion was clubbed to death and thrown into the cloaca maxima, the main sewer of ancient Rome. The date usually attributed to his martyrdom is 288 AD. He was buried in the catacombs but in the early 4th century his body was moved to the Basilica Apostolorum, later renamed the basilica of St Sebastian outside the Walls (San Sebastiano fuori le Mura). Saint Ambrose spoke of his martyrdom in a sermon in Milan the 4th century and by the middle of that century, 354 AD, his feast day appears in a church calendar. The 450 AD Acts of Saint Sebastian and the 14th century Legenda Aurea record his mythology in detail.

In the early centuries of Christianity, many saints were invoked against the plague but in the 7th century, two interventions by Sebastian were recorded. A 'pernicious and severe pestilence' in Rome in 680 AD miraculously ceased following the erection of an altar in San Pietro in Vincoli and the invocation of St Sebastian. Paul the Deacon in 680 recorded a similar occurrence in his Historia Longobardum, but this time occurring in Pavia, relics of the saint having been brought from Rome. Thereafter Sebastian's aid was particularly sought in this regard. The bubonic plague was often represented as conveyed by arrows, rained down from heaven by God the Father. There is thus a further connection between the plague and the first martyrdom of Sebastian. In addition there is a mythological connection, through the arrow, with the god Apollo. The arrow was one of the symbols of the Apollo who both brought and protected people from the plague. It was natural then that as bubonic plague swept its way across Europe in epidemic after epidemic for nearly 1,000 years for Sebastian to become the principal saint to be called on for help to ward off this evil. His claim for this role was the greater because, according to the legend, Sebastian had survived the arrows, being martyred later in a different way.

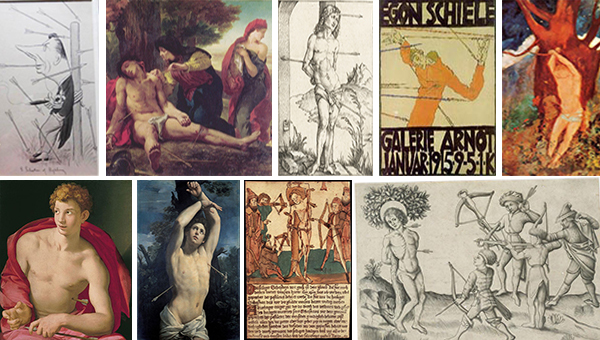

The earliest known representation of Sebastian, now surviving only as a black and white photograph, was a 5th century fresco in the crypt of St Cecilia in the catacomb of St Callistus. The oldest still surviving representation is a 6th century mosaic in the church of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Classe, near Ravenna. A further important early representation is a mosaic in San Pietro in Vincoli, dating from 680 AD. For many centuries Sebastian was shown as a mature man, clothed, sometimes in the garb of a Roman soldier and sometimes holding an arrow. However as the Renaissance mood stole across Europe, he began to take on a different role. He was transformed into a young and beautiful male and the Renaissance ideal of beauty found in him the perfect representative. Sebastian became part of the Renaissance emulation of the antique. He appears beautiful and naked or near naked, in large numbers of paintings. Sometimes he resembled Apollo. Sometimes, when clothed, he sheltered the faithful from the plague-bearing arrows by catching them in his cloak, a role on other occasions played by the Virgin Mary. Sebastian became the patron saint of soldiers and archers. Almost all the great artists portrayed him, some of them on many occasions. From the Renaissance onwards, he embodied the combination of ecstasy and sexuality, so much a part of many deep religious feelings. Male beauty provided the basis for another layer of meaning: the sexual ambiguity of the Roman soldiery struck a chord for those seeking to glorify the male body for entirely human motives. Il Sodoma was not only a celebrated artist but also an acknowledged homosexual and more than once he painted Sebastian with deep sensuality. Following the counter reformation and the Council of Trent (1545-1563) , such depictions were greatly frowned upon.

Meanwhile the plague theme remained and the gratitude of princes and people came to show itself in a new way in the erection of plague columns in town centres in Germany, Austria and Hungary. These areas, with much more of a sculptural tradition, also produced many carvings of him in marble and wood, and sculptures in silver and bronze. In this way his importance in art lasted well beyond the Renaissance.

The eventual defeat of the plague and the movement from centre stage of religious art combined, however, to produce the sudden demise of Sebastian. And yet he remained in the cultural subconscious to be called upon by such diverse figures as Corot, embellishing his soft trees and colours with a religious motif; Redon, Kokoschka, Moreau and Schiele finding in Sebastian an expressionist symbol.

The iconography of Sebastian includes the usual attribute of a Christian saint, the halo. More specifically he has the attributes of a Christian martyr, in early works a small cross and in later works the martyr's palm (derived from the victor's palm, carried in military triumphs in the ancient world) and the victor's crown. The crown may have the form of a laurel wreath, alluding to the laurel wreath of Apollo and of victors in battle. More specifically, Sebastian has the attributes of a Christian soldier ‒ a sword and the garb of a roman soldier. In addition to these general attributes of the saint, the martyr and the soldier, Sebastian has very specific symbols. In first place is the arrow, sometimes with the addition of a quiver or a bow. He may be pierced by arrows or may hold his attribute or present it to the virgin, or an angel may hold his arrow. There may also be a pillar or a tree to which he is tied, linking him visually to the flagellation and later crucifixion of Christ. The pillar is one of the symbols of the Passion and Christ was crucified on the 'the tree of the cross'. The wounds and shed blood of Sebastian also link him visually to Christ. Sometimes the image of a pieta is adapted to show Sebastian succoured by Irene and other virtuous women. And yet paganism is lurking again. The arrow is not only a symbol of Christian ecstasy but also from ancient times has been not only an attribute of Apollo and a bringer of plague but also a phallic symbol and a symbol of pagan love. The tree is likewise a visual link not only to Christ but also to Maryas. The pillar associates Sebastian not only with ancient Rome but also ancient Greece. Sebastian is often paired with other plague saints, particularly Saint Roch, but also … Less often he is accompanied by other medical or physician saints such as Saint Anthony and Saints Cosmas and Damian.